I’m deep into my class, dealing with science and technology, and the cultural changes they bring about. As usual, questions of technology and lifestyle come up among my students. Here are some common memes, complaints, observations. Depending on where you stand on the spectrum — how much technology is too much?

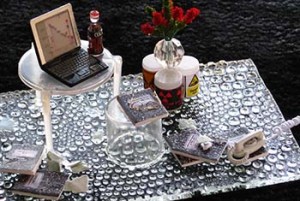

1. I don’t have time anymore to smell the roses, says one student.

My question: how much time does it take to smell roses to get the full benefit of the scent? One good long inhalation should do it. And the rest of the time, we can be doing something useful, something that might even benefit our fellows/sisters next door.

2. Math skills are going away — a clerk doesn’t even have to “make change” anymore!

My response: So what? Is that what we aspire to for our kids, to be whizzes at arithmetic? Or do we want them to dream up new software or perhaps new medical devices, or write brilliant novels? Horse riding skills are going away also, now that we have planes, trains, and automobiles. Do we lament that as well?

3. Penmanship, too, has suffered – no more cursive!

Another so what? Hasn’t it always been easier to print? Isn’t that why forms usually state PLEASE PRINT? Because it’s hard to read a cursive? Isn’t there something more creative to do than write a beautiful letter A? Monks did this, but they didn’t have much else to do.

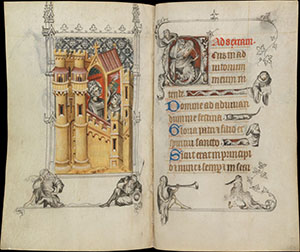

The Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux, Queen of France, ca. 1324–28, Grisaille, tempera, and ink on vellum, the Cloisters

Maybe we leave it to today’s artists to create more fonts or illustrate manuscripts.

We’re not necessarily dumber because we don’t need certain outdated skills. Neither are we more stressed if we don’t “stop to appreciate the beauty of life,” as so many memes remind us.

Some of us, in fact, become very stressed when we don’t have enough to do. For me, panic sets in when I have fewer than 7 projects underway.

Finally, it’s not the Internet’s fault that we’re distracted (from what? the roses?) We use cars instead of horses; therefore we can go more places, educate ourselves on the way. Yes, FB and other Internet attractions can grab us and “waste” time, but that’s our choice, and I feel — for me — if I didn’t have the Internet to distract me, something else would!

It’s my personality/temperament that’s to blame, not the technology in front of me.

You?

Filed Under :

Filed Under :  Oct.11,2018

Oct.11,2018

Tags :

Tags :